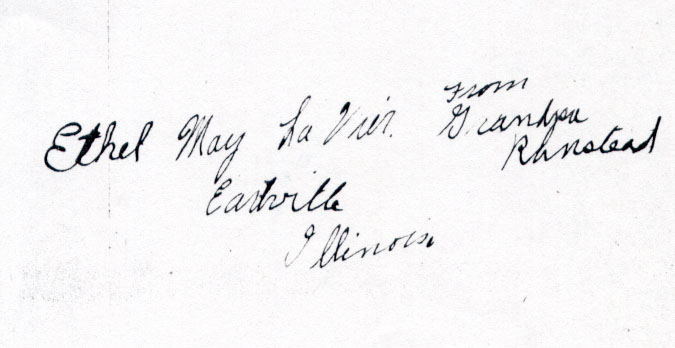

"In memory of Ethel Hagi"

Submitted by Nicholas Konz, Jr.

Transcribed by: Mary Jane Fitzpatrick

| Name of Place |

Distance

|

Date of Arrival | Departure |

| Ottawa | February 27 | ||

| Chicago |

75

|

February 27, 1862 | March 23 |

| St. Louis, Mo |

250

|

March 24 | March 25 |

|

180

|

March 26 | March 27 | |

| Savannah, Tenn |

250

|

March 28 | April 7 |

| Pittsburg Landing |

7

|

April 7 | April 26 |

| Corinth |

30

|

May 30 | June 2 |

| Grand Junction |

47

|

June 15 | June 25 |

| LaGrange |

4

|

June 25 | July 5 |

| Holly Springs, Miss |

25

|

July 4 | July 5 |

| LaGrange, Tenn |

25

|

July 7 | July 17 |

| Moscow |

10

|

July 17 | July 18 |

| LaFayette |

10

|

July 18 | July 19 |

| Germantown |

15

|

July 19 | July 20 |

| Memphis |

15

|

July 21 | September 6 |

| Bolivar |

100

|

September 13 | September 20 |

| Near Grand Junction |

18

|

September 20 | September 21 |

| Bolivar |

18

|

September 21 | October 4 |

| Hatchie River |

30

|

October 4 | October 7 |

| Bolivar |

30

|

October 8 | November 3 |

| LaGrange, Tenn |

23

|

November 4 | November 6 |

| Lamar, Miss |

11

|

November 6 | November 6 |

| LaGrange, Tenn |

11

|

November 7 | November 8 |

| Lamar, Miss |

16

|

November8 | November 9 |

| LaGrange, Tenn |

11

|

November 9 | November 23 |

| Somerville |

14

|

November 23 | November 23 |

| LaGrange, Tenn |

14

|

November 23 | November 28 |

| Holly Springs, Miss |

25

|

November 29 | November 30 |

| Waterford |

10

|

November 30 | December 11 |

| Oxford |

20

|

December 22 | December 24 |

| Tallahatchie Fort |

11

|

December 24 | December 29 |

| Holly Springs, Miss |

18

|

January 5, 1863 | January 10 |

| Moscow, Tenn |

25

|

January 5 | March 9 |

| LaFayette |

10

|

March 9 | March 9 |

| Colliersville |

6

|

March 9 | March 10 |

| Germantown |

10

|

March 10 | March 10 |

| Bridgewater |

5

|

March 10 | March 10 |

| Memphis |

14

|

March 11 | May 17 |

| Young's Point, Miss |

280

|

May 19 | May 20 |

| Haines Bluff |

25

|

May 20 | May 24 |

| Vicksburg |

20

|

May 25 | July 5 |

| Clinton |

40

|

July 9 | July 10 |

| Jackson |

10

|

July 10 | July 21 |

| Raymond |

20

|

July 21 | July 22 |

| Vicksburg |

35

|

July 23 | August 18 |

| Milldale |

10

|

December 3 | |

| Milldale | 1864 | January 31 | |

| Big Black |

6

|

January 31 | February 3 |

| Clinton |

30

|

February 4 | February 5 |

| Jackson |

10

|

February 6 | February 7 |

| Brandon |

13

|

February 7 | February 8 |

| Morton |

25

|

February 9 | February 10 |

| Hillsboro |

13

|

February 10 | February 10 |

| Decatur |

25

|

February 13 | February 25 |

| Meridian |

34

|

February 15 | February 16 |

| Enterprise |

18

|

February 16 | February 19 |

| Near Meridian |

20

|

February 19 | February 20 |

| Decatur |

26

|

February 21 | February 22 |

| Hillsboro |

25

|

February 23 | February 24 |

| Canton |

37

|

February 27 | February 29 |

| Livingston |

12

|

February 29 | February 29 |

| Heyersville |

20

|

March 1 | March 2 |

| Big Black |

23

|

March 2 | March 13 |

| Vicksburg |

10

|

March 13 | March 14 |

| Memphis |

280

|

March 18 | March 18 |

| Cairo, Ill |

250

|

March 20 | March 21 |

| LaSalle |

315

|

March 23 | March 23 |

| Ottawa |

16

|

March 23 | April 29 |

| Peoria |

115

|

April 29 | April 30 |

| Havana |

55

|

April 30 | April 30 |

| St.Louis, Mo |

125

|

May 1 | May 2 |

| Cairo, Ill |

180

|

May 3 | May 10 |

| Paducah, Ky |

80

|

May 11 | May 12 |

| Clifton, Tenn |

230

|

May 14 | May 16 |

| Waynesboro |

16

|

May 16 | May 17 |

| Lawrenceburg |

30

|

May 18 | May 18 |

| Pulaski |

20

|

May 19 | May 21 |

| Elkwood |

15

|

May 21 | May 21 |

| Huntsville, Ala |

33

|

May 23 | May 25 |

| Decatur |

28

|

May 26 | May 27 |

| Somerville |

24

|

May 28 | May 29 |

| Warrentown |

32

|

May 31 | May 31 |

| VanBuren |

32

|

June 2 | June 3 |

| Cedar Bluffs |

17

|

June 3 | June 4 |

| Missionary Station |

14

|

June 4 | June 5 |

| Rome, Ga |

18

|

June 5 | June 6 |

| Kingston |

15

|

June 6 | June 7 |

| Carterville |

10

|

June 7 | June 7 |

| Allatoona |

7

|

June 7 | July 13 |

| Ackworth |

6

|

July 13 | July 14 |

| Big Shanty |

1

|

July 14 | July 14 |

| Marietta |

5

|

July 14 | July 17 |

| Roswell |

15

|

July 17 | July 17 |

| Decatur |

18

|

July 19 | July 20 |

| Near Atlanta |

5

|

July 20 | August 25 |

| Fairtown |

25

|

August 28 | August 30 |

| Near Jonesboro |

14

|

August 31 | September 2 |

| Near Lovejoy |

8

|

September 2 | September 5 |

| Jonesboro |

8

|

September 5 | September 7 |

| East Point |

11

|

September 8 | October 1 |

| Fairtown |

16

|

October 2 | October 2 |

| East Point |

18

|

October 3 | October 4 |

| Near Marietta |

22

|

October 5 | October 7 |

| Powder Springs |

10

|

October 7 | October 7 |

| Near Lost Mountain |

5

|

October 7 | October 8 |

| Powder Springs |

10

|

October 8 | October 8 |

| Marietta |

15

|

October 9 | October 9 |

| Big Shanty |

5

|

October 9 | October 11 |

| Ackworth |

2

|

October 11 | October 11 |

| Allatand |

6

|

October 11 | October 11 |

| Carterville |

7

|

October 12 | October 12 |

| Kingston |

10

|

October 12 | October 12 |

| Near Rome |

10

|

October 12 | October 12 |

| Dairsville |

12

|

October 13 | October 14 |

| Resacca |

23

|

October 14 | October 15 |

| Snake Creek Gap |

12

|

October 15 | October 16 |

| LaFayette |

20

|

October 18 | October 18 |

| Somerville |

13

|

October 19 | October 19 |

| Alpine |

10

|

October 19 | October 20 |

| Galesville, Ala |

15

|

October 20 | October 28 |

| Missionary Station |

16

|

October 28 | October 29 |

| Rome, Ga |

14

|

October 29 | October 31 |

| Cedarville |

20

|

November 1 | November 2 |

| Vanwert |

14

|

November 2 | November 3 |

| Dallas |

15

|

November 3 | November 4 |

| Near Lost Mountain |

9

|

November 4 | November 5 |

| Marietta |

15

|

November 6 | November 13 |

| Atlanta |

22

|

November 14 | November 15 |

| McDonough |

35

|

November 16 | November 17 |

| Osmulgee Mills |

31

|

November 18 | November 19 |

| Monticello |

11

|

November 19 | November 19 |

| Hillsboro |

9

|

November 20 | November 20 |

| Gordon |

28

|

November 21 | November 22 |

| Irvington |

11

|

November 22 | November 23 |

| Tombsboro |

6

|

November 23 | November 23 |

| Oconea River |

7

|

November 23 | November 25 |

| Tombsboro |

7

|

November 25 | November 25 |

| Ball's Ferry |

8

|

November 26 | November 26 |

| Sabastapol |

55

|

November 31 | December 1 |

| Burton |

6

|

December 2 | December 2 |

| Millen |

13

|

December 2 | December 3 |

| Scarboro |

7

|

December 3 | December 4 |

| Oliver |

11

|

December 5 | December 7 |

| Egypt |

5

|

December 7 | December 7 |

| Brewer |

6

|

December 7 | December 7 |

| Gayton |

7

|

December 7 | December 7 |

| Marlow |

6

|

December 8 | December 8 |

| Eden |

7

|

December 8 | December 9 |

| Feoler |

11

|

December 9 | December 10 |

| Near Savannah |

6

|

December 10 | December 11 |

| Cross Keyes |

10

|

December 12 | December 16 |

| Kings Bridge |

5

|

December 15 | December 24 |

| Near Savannah |

17

|

December 24 | |

| Near Savannah | January 1865 | January 6 | |

| Hilton Head. S. C. |

55

|

January 6 | January 6 |

| Beaufort |

22

|

January 6 | January 13 |

| Pocotaligo |

26

|

January 16 | January 20 |

| Combabee River |

6

|

January 20 | January 23 |

| Pocotaligo |

6

|

January 23 | January 29 |

| McPhersonville |

8

|

January 29 | January 30 |

| River Bridge |

23

|

February 2 | February 6 |

| Midway |

19

|

February 7 | February 9 |

| Orangeburg |

24

|

February 12 | February 13 |

| Louisville |

17

|

February 14 | February 14 |

| Columbus |

42

|

February 19 | February 19 |

| Disco |

21

|

February 20 | February 21 |

| Ridgeway |

6

|

February 21 | February 21 |

| Wimisboro |

13

|

February 22 | February 22 |

| Paws Ferry |

17

|

February 23 | February 23 |

| Liberty Hill |

6

|

February 23 | February 24 |

| Sharon |

74

|

March 3 | March 5 |

| Bennettsville |

15

|

March 6 | March 7 |

| Florenece College |

25

|

March 9 | March 9 |

| Fayetteville, N.C. |

37

|

March 11 | March 13 |

| Blocksville |

18

|

March 16 | March 16 |

| Owensville |

10

|

March 16 | March 17 |

| Bentonville |

48

|

March 20 | March 23 |

| Goldsboro |

18

|

March 24 | April 10 |

| Raleigh |

62

|

April 14 | April 15 |

| Page's Station |

8

|

April 15 | April 19 |

| Near Raleigh |

5

|

April 19 | April 25 |

| Forrestville |

20

|

May 1 | May 1 |

| Clarksville Junction |

91

|

May 3 | May 3 |

| Ridgway |

4

|

May 3 | May 3 |

| Warrenton |

5

|

May 3 | May 3 |

| Robertson's Ferry |

13

|

May 4 | May 4 |

| Petersburg, Va. |

70

|

May 7 | May 8 |

| Manchester |

21

|

May 10 | May 12 |

| Richmond |

4

|

May 12 | May 12 |

| Fredericksburg |

70

|

May 16 | May 16 |

| Alexandria |

62

|

May 24 | May 24 |

| Fort Henry |

4

|

May 24 | June 7 |

| Relay House, Md. |

30

|

June 7 | June 7 |

| Harper's Ferry, Va. |

70

|

June 8 | June 8 |

| Piedmont |

120

|

June 8 | June 8 |

| Grafton |

86

|

June 9 | June 9 |

| Parkersburg |

112

|

June 10 | June 10 |

| Gillipolis, Ohio |

115

|

June 10 | June 10 |

| Cincinnati |

190

|

June 11 | June 11 |

| Louisville, Ky |

145

|

June 12 | ........... |